On 2018-January-04, following a week of security and privacy events in Germany, I left Berlin for the United States via a connecting flight in Norway. I had spent most of my time in Germany at the 34th CCC (34C3) in Leipzig, and I was headed to New York to help Calyx Institute with some work that they and Emerald Onion are working on.

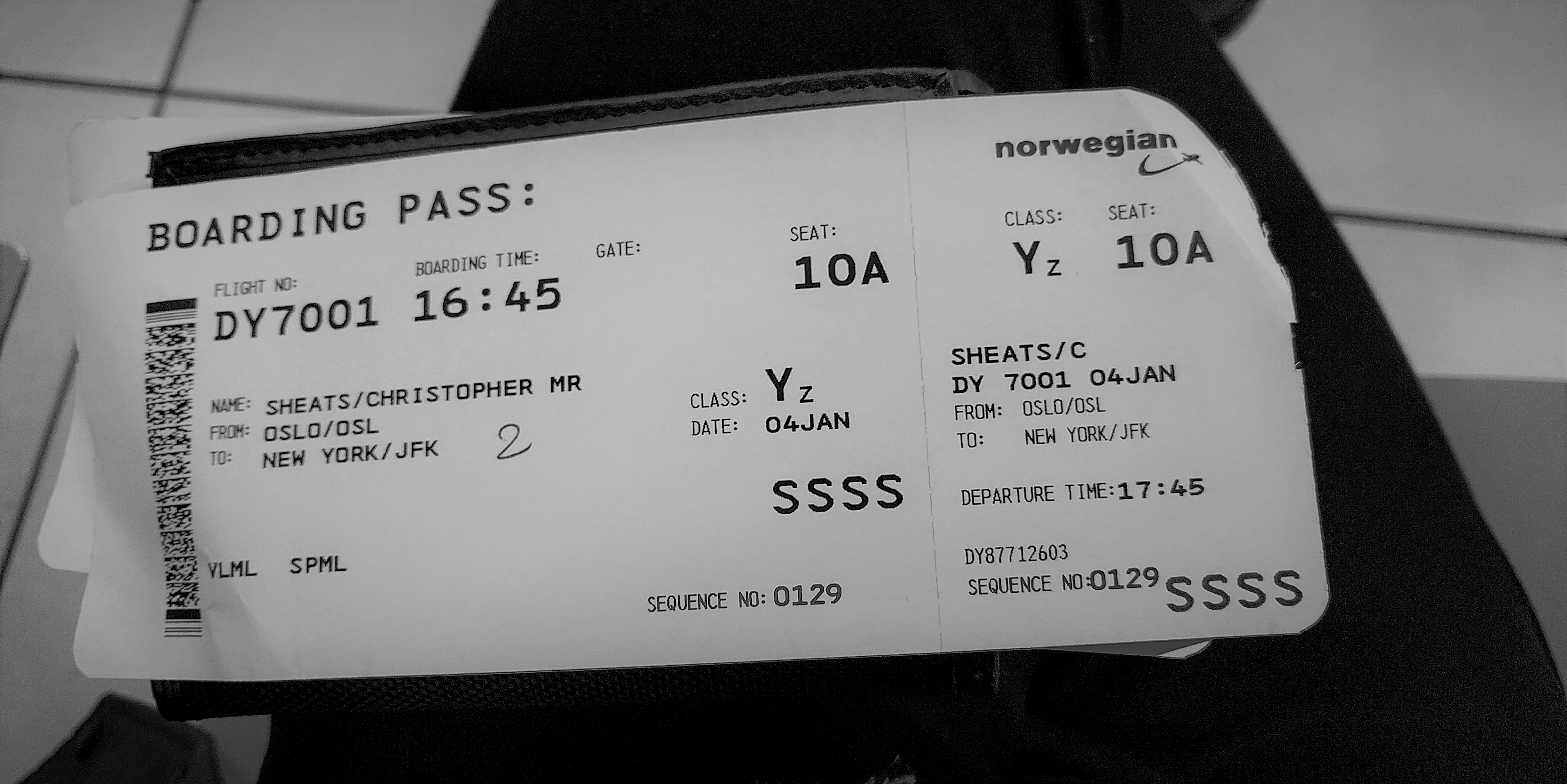

Upon getting to Berlin Schönefeld Airport (SXF), I checked in by visiting the Norwegian airline ticket counter. As expected, I received two tickets, one for my layover trip from Berlin (SXF) to Oslo (OSL), and another ticket for my flight from Oslo (OSL) to New York (JFK). On my ticket from Oslo to New York, I promptly noticed the “SSSS” in large, capital letters.

I was fortunate enough to be provided this clear warning. If you’re a high priority target, you probably won’t be so lucky. It is likely that if you are going to get SSSS, you won’t be able to pre-check online prior to your arrival, but, unfortunately, I didn’t attempt to pre-check on this occasion.

I set the “why” aside and immediately started thinking about mitigation and avoidance scenarios. In the information security space, this was like being alerted beforehand that a specific malicious actor with specific capabilities was going to be toying with me, my devices, and data. This was a gift.

SSSS has different severity levels, as there is some percentage of secondary screenings that are actually random. It’s up to you to plan for the worst. In addition to coming back into the United States, it is fairly well known that foreign nationals leaving the United States from conferences like DEF CON and Black Hat have a much higher probability to be hit with SSSS. Be prepared.

Experience

My secondary screening took place at the departure gate before boarding the plane to New York. I handed my boarding ticket with SSSS to the receptionist who scanned my ticket. The light flashed red, and she explained that I had been chosen for a random security screening. She took my passport and told me she would be keeping it until I finished the screening. The receptionist had a small stack of passports with her at the desk with no physical security aside from her looking at them. I verified with the receptionist that I would not be in possession of my passport until completed the screening.

The receptionist handed me off another security person with a clipboard. I observed the agent and the information on the clipboard. I had enough time to read through half the list, but intuitively decided not to commit any personal information to memory. Based on the data on the clipboard, there were 28 passengers who were “randomly” selected for secondary screening from a near full flight of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner. The list had women and men on it, and listed their first and last names, their gender (“Ms” and “Mr”, presumably based on info provided when purchasing the ticket), the originating airport and the destination airport.

The agent with the clipboard circled something on the line with my name and had me stand in a line that lead off to a private screening area. A third security agent came up behind me within a minute of standing in line and asked me to come into the room with him. He had me take off my bags but not my heavy parka, and had me take off my shoes. I was asked to verify my first and last name. I was asked to hold out my hands for a swab used for detecting chemicals used in explosives. The same swab was used for the outside and inside of my shoes. I was asked if I had any electronic tablets or computers. I took out my Surface and he used the swab on it, too. I was not asked to turn on the device.

The agent stated that I could put my shoes back on and after the swab analyzing machines displayed green that I could go, and I joked that if it turned red he’d be making some calls. He laughed and agreed. When leaving the private screening area, there were two people waiting in line for the secondary screening. I was told to go and speak to the first security agent (the receptionist) to get my passport, unescorted. After being handed my passport back, I tied my shoes and got on the plane.

My SSSS experience appeared to be random but I found evidence against that. There were 272 people who were flying from Oslo to New York, and 28 were on the SSSS list. I confirmed with one other person that they, too, attended 34C3 in Leipzig, Germany. A second person, from Twitter, also confirmed that they attended 34C3 and received SSSS on their way back to the United States.

Capability

Interestingly, also on 2018-January-04, the United States Department of Homeland Security, Customs and Border Patrol released an update to their Directive for Border Search of Electronic Devices:

- CBP Directive No. 3340-049A: https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2018-Jan/cbp-directive-3340-049a-border-search-electronic-media.pdf

Just a week earlier, Kurt Opsahl and William Budington of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) presented at 34C3 on this exact topic:

- Protecting Your Privacy at the Border, Traveling with Digital Devices in the Golden Age of Surveillance: https://media.ccc.de/v/34c3-9086-protecting_your_privacy_at_the_border

Legal Theory

I was traveling with a personal computer with Emerald Onion business secrets, like service account information, operational data from random technical and administrative chats (that are otherwise end-to-end encrypted), and client-privileged communications. However, my knowledge of my rights were limited being outside the United States.

When traveling, there are two questions: Who is searching you, and what are your rights in those instances?

There are three categories of entities that may search you.

The first is the United States Government (USG). If a USG official is searching you, you have constitutional protections. The second is a private company. If a private company is searching you under the direction of the USG, then you may have constitutional rights. The third category is foreign governments, which are subject to their own laws and search analyses.

In the US, as a US citizen, your rights generally come from the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution, which enshrines the right to be free from unreasonable search and seizures. Inherent in this is that, if the search is reasonable, then it is not a violation of the Fourth Amendment.

Searches at the border have more leeway for reasonableness, as the USG is seen as having an increased interest in searching those entering in our borders, often called the border search exception. This is why electronic devices can more easily be searched at the border, whereas once inside the US, there would be more stringent requirements.

However, privacy rights still exist despite the border search exemption. The search still must be reasonable, it’s just the reasonableness bar is very low. There are also certain privileges that exist, such as attorney-client privilege, and trade secrets and similar intellectual privacy privileges. The government cannot legally force you to waive these rights, which is in fact the purpose of them.

Another right citizens have is the right to enter the US. A US citizen, almost always (except, potentially, in extreme circumstances like being an unlawful enemy combatant) has the right to enter the US. Therefore, US citizens can always refuse to give up their passwords or access to their devices, and still assert their right to return home. However, US border agents can still seize your devices and hold you for a period of time.

There are many legal reasons why you can push back at a border search. However, the question remains: how much do you want to push back? Border officials can legally do invasive things, such as seize your electronics and detain you for a significant period of time.

Technical Preparation

Tails Linux is always my favorite for traveling across borders. Tails is stateless, aside from small amounts of encrypted data in my (opt-in) persistent storage. However, I know that if any of my devices, USB included, leave my person and sight, they have to be distrusted and burned. Auto-torifying network traffic makes it easy for me to download or upload high value data from onion addresses via ssh and rsync, and I don’t need to deal with any untrustworthy VPN agents or infrastructure.

Static self-hosted VPN infrastructure isn’t trustworthy, especially when you’re a target. Commercial, single-agent operated, cloud-based (other people’s computers) VPNs can never be trustworthy, despite people’s strong desires for them to be.

Some useful points:

- Before leaving home, I backed up my data to other encrypted devices.

- I don’t travel with access to systems or authenticated communication mediums I do not need.

- With proper 2FA and unmemorable passphrases, if I were asked to provide access credentials to specific accounts, I could tell the truth (don’t ever lie to a federal agent, anywhere) and yet wouldn’t be able to comply with the disclosure of account credentials. The 2FA (Yubikey, OTP device, etc) are kept at home in a trusted, safe place.

- I don’t travel with a full list of contacts. No need to jeopardize the security and privacy of friends, family, etc if you won’t need to contact them during a short trip.

Technical Response

When going through mental scenarios, it occurred to me that there were two specific features that I would have liked to have in my chosen password manager:

- A panic button (meaningful obliteration of data, but fortunately with Tails Linux, this is less important)

- Functionality to support onion-hosted databases and key files

When first recognizing SSSS, I immediately thought about wiping some devices and even burning them before going through security. I refrained from doing this, but I later confirmed that, in this specific scenario, I did have the right to wipe or destroy devices. It felt like I did not have a right to do this since I am not a Norwegian citizen and thus I did not have any known protected rights in the country where the secondary screening took place, and more importantly, had no prior knowledge of which organization is performing the screening.

I focused on several preemptive tasks based on my limited access and knowledge:

- People: alerting the people that I had secure access to about the anticipated breach (oh and Tweeting about it)

- Device access: shutting the devices down and depending on hardware initialization and kernel boot security

- Keybase groups: revoking the devices I was carrying

- Signal groups: informing the participants the nature of the event, deleting the group itself, unregistering the number then deleting Signal

- Password databases: shredding the database file and physically disposing of the corresponding key file

Looking forward

It’s important for technical folks, who have privileged access to presumably secure digital systems, to be aware of this type of physical, government surveillance. It’s also important to talk about this type of stuff with your co-workers, family, and friends. If you have contacts who are activists, journalists, or lawyers who are also likely to travel with sensitive data, please have conversations with them about this stuff, too!